Claude Debussy On Flowvella

Early life Achille Claude Debussy was born on August 22, 1862, in St-Germain-en-Laye, France. He was the oldest of five children. His father, Manuel-Achille Debussy, ran a china shop and had a hard time making ends meet. Debussy began taking piano lessons at age seven and entered the Paris Conservatory (school of fine arts) in Paris, France, at the age of ten. His instructors and fellow students recognized that he had talent, but they thought some of his attempts to create new sounds were odd. In 1880 Nadezhda von Meck, who had helped support Russian composer Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893).

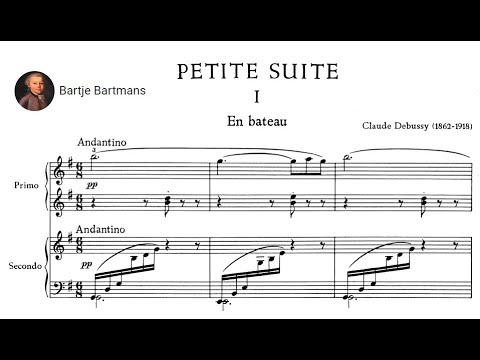

Debussy in 1908 Achille-Claude Debussy ( French:; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born to a family of modest means and little cultural involvement, Debussy showed enough musical talent to be admitted at the age of ten to France's leading music college, the. He originally studied the piano, but found his vocation in innovative composition, despite the disapproval of the Conservatoire's conservative professors. He took many years to develop his mature style, and was nearly 40 before achieving international fame in 1902 with the only opera he completed,.

Debussy's orchestral works include (1894), (1897–1899) and (1905–1912). His music was to a considerable extent a reaction against and the German musical tradition.

He regarded the classical as obsolete and sought an alternative in his 'symphonic sketches', (1903–1905). His piano works include two books of and two of. Throughout his career he wrote based on a wide variety of poetry, including his own. He was greatly influenced by the poetic movement of the later 19th century. A small number of works, including the early and the late have important parts for chorus. In his final years, he focused on chamber music, completing three of six planned sonatas for different combinations of instruments. With early influences including Russian and far-eastern music, Debussy developed his own style of harmony and orchestral colouring, derided – and unsuccessfully resisted – by much of the musical establishment of the day.

Claude Debussy On Flowvellas

His works have strongly influenced a wide range of composers including, and the jazz pianist and composer. Debussy died from at his home in Paris at the age of 55 after a composing career of a little more than 30 years.

Debussy by, 1884 At the end of 1880 Debussy, while continuing in his studies at the Conservatoire, was engaged as accompanist for Marie Moreau-Sainti's singing class; he took this role for four years. Among the members of the class was Marie Vasnier; Debussy was greatly taken with her, and she inspired him to compose: he wrote 27 songs dedicated to her during their seven-year relationship. She was the wife of Henri Vasnier, a prominent civil servant, and much younger than her husband. She soon became Debussy's mistress as well as his muse. Whether Vasnier was content to tolerate his wife's affair with the young student or was simply unaware of it is not clear, but he and Debussy remained on excellent terms, and he continued to encourage the composer in his career. At the Conservatoire, Debussy incurred the disapproval of the faculty, particularly his composition teacher, Guiraud, for his failure to follow the orthodox rules of composition then prevailing.

Nevertheless, in 1884 Debussy won France's most prestigious musical award, the, with his. The Prix carried with it a residence at the, the, to further the winner's studies. Debussy was there from January 1885 to March 1887, with three or possibly four absences of several weeks when he returned to France, chiefly to see Marie Vasnier. Initially Debussy found the artistic atmosphere of the Villa Medici stifling, the company boorish, the food bad, and the accommodation 'abominable'. Neither did he delight in Italian opera, as he found the operas of and not to his taste.

He was much more impressed by the music of the 16th-century composers and, which he heard at: 'The only church music I will accept.' He was often depressed and unable to compose, but he was inspired by, who visited the students and played for them.

In June 1885, Debussy wrote of his desire to follow his own way, saying, 'I am sure the Institute would not approve, for, naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one. But there is no help for it! I am too enamoured of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!'

Debussy finally composed four pieces that were submitted to the Academy: the symphonic ode Zuleima (based on a text by ); the orchestral piece Printemps; the cantata (1887–1888), the first piece in which the stylistic features of his later music began to emerge; and the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra, which was heavily based on Franck's music and was eventually withdrawn by Debussy. The Academy chided him for writing music that was 'bizarre, incomprehensible and unperformable'. Although Debussy's works showed the influence of, the latter concluded, 'He is an enigma.' During his years in Rome Debussy composed – not for the Academy – most of his cycle, which made little impact at the time but was successfully republished in 1903 after the composer had become well known. Return to Paris, 1887 A week after his return to Paris in 1887, Debussy heard the first act of 's at the, and judged it 'decidedly the finest thing I know'. In 1888 and 1889 he went to the annual festivals of Wagner's operas at.

He responded positively to Wagner's sensuousness, mastery of form, and striking harmonies, and was briefly influenced by them, but, unlike some other French composers of his generation, he concluded that there was no future in attempting to adopt and develop Wagner's style. He commented in 1903 that Wagner was 'a beautiful sunset that was mistaken for a dawn'. Emma Bardac (later Emma Debussy) in 1903 In 1903 there was public recognition of Debussy's stature when he was appointed a Chevalier of the, but his social standing suffered a great blow when another turn in his private life caused a scandal the following year.

Among his pupils was Raoul Bardac, son of, the wife of a Parisian banker, Sigismond Bardac. Raoul introduced his teacher to his mother, to whom Debussy quickly became greatly attracted. She was a sophisticate, a brilliant conversationalist, an accomplished singer, and relaxed about marital fidelity, having been the mistress and muse of a few years earlier. After despatching Lilly to her parental home at Bichain in on 15 July 1904, Debussy took Emma away, staying incognito in and then at in Normandy.

He wrote to his wife on 11 August from, telling her that their marriage was over, but still making no mention of Bardac. When he returned to Paris he set up home on his own, taking a flat in a different. On 14 October, five days before their fifth wedding anniversary, Lilly Debussy attempted suicide, shooting herself in the chest with a revolver; she survived, although the bullet remained lodged in her for the rest of her life. The ensuing scandal caused Bardac's family to disown her, and Debussy lost many good friends including Dukas and Messager.

His relations with Ravel, never close, were exacerbated when the latter joined other former friends of Debussy in contributing to a fund to support the deserted Lilly. The Bardacs divorced in May 1905.

Finding the hostility in Paris intolerable, Debussy and Emma (now pregnant) went to England. They stayed at the in July and August, where Debussy corrected the proofs of his symphonic sketches, celebrating his divorce on 2 August.

After a brief visit to London, the couple returned to Paris in September, buying a house in a courtyard development off the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne (now ), Debussy's home for the rest of his life. See also: and In a survey of Debussy's oeuvre shortly after the composer's death, the critic wrote, 'It would be hardly too much to say that Debussy spent a third of his life in the discovery of himself, a third in the free and happy realisation of himself, and the final third in the partial, painful loss of himself'. Later commentators have rated some of the late works more highly than Newman and other contemporaries did, but much of the music for which Debussy is best known is from the middle years of his career. The analyst David Cox wrote in 1974 that Debussy, admiring Wagner’s attempts to combine all the creative arts, 'created a new, instinctive, dreamlike world of music, lyrical and pantheistic, contemplative and objective – a kind of art, in fact, which seemed to reach out into all aspects of experience.' In 1988 the composer and scholar wrote of Debussy: Because of, rather than in spite of, his preoccupation with chords in themselves, he deprived music of the sense of harmonic progression, broke down three centuries' dominance of harmonic tonality, and showed how the melodic conceptions of tonality typical of primitive folk-music and of medieval music might be relevant to the twentieth century' Debussy did not give his works, apart from his String Quartet op.

10 in G minor (also the only work where the composer's title included a ). His works were catalogued and indexed by the musicologist in 1977 (revised in 2003) and their ('L' followed by a number) is sometimes used as a suffix to their title in concert programmes and recordings. Early works, 1879–1892. Performed by Ivan Ilic Problems playing these files? Among the late piano works are two books of (1909–10, 1911–13), short pieces that depict a wide range of subjects. Lesure comments that they range from the frolics of minstrels at Eastbourne in 1905 and the American acrobat 'General Lavine' 'to dead leaves and the sounds and scents of the evening air'.

(In white and black, 1915), a three-movement work for two pianos, is a predominantly sombre piece, reflecting the war and national danger. The (1915) for piano have divided opinion. Writing soon after Debussy's death, Newman found them laboured – 'a strange last chapter in a great artist's life'; Lesure, writing eighty years later rates them among Debussy's greatest late works: 'Behind a pedagogic exterior, these 12 pieces explore abstract intervals, or – in the last five – the sonorities and timbres peculiar to the piano.' In 1914 Debussy started work on a planned set of for various instruments.

His fatal illness prevented him from completing the set, but those for cello and piano (1915), flute, viola and harp (1915), and violin and piano (1917 – his last completed work) are all concise, three-movement pieces, more in nature than some of his other late works. (1911), originally a five-act musical play to a text by that took nearly five hours in performance, was not a success, and the music is now more often heard in a concert (or studio) adaptation with narrator, or as an orchestral suite of 'Fragments symphoniques'. Debussy enlisted the help of in orchestrating and arranging the score. Two late stage works, the ballets (1912) and (1913), were left with the orchestration incomplete, and were completed by and Caplet, respectively. Style Debussy and Impressionism.

's (1872), from which 'Impressionism' takes its name The application of the term 'Impressionist' to Debussy and the music he influenced has been much debated, both in the composer's lifetime and subsequently. The analyst writes that Impressionism was originally a term coined to describe a, typically scenes suffused with reflected light in which the emphasis is on the overall impression rather than outline or clarity of detail, as in works by, and others. Langham Smith writes that the term became transferred to the compositions of Debussy and others which were 'concerned with the representation of landscape or natural phenomena, particularly the water and light imagery dear to Impressionists, through subtle textures suffused with instrumental colour'. Among painters, Debussy particularly admired, but also drew inspiration from. With the latter in mind the composer wrote to the violinist in 1894 describing the orchestral Nocturnes as 'an experiment in the different combinations that can be obtained from one colour – what a study in grey would be in painting.'

Debussy strongly objected to the use of the word 'Impressionism' for his (or anybody else's) music, but it has continually been attached to him since the assessors at the Conservatoire first applied it, opprobriously, to his early work Printemps. Langham Smith comments that Debussy wrote many piano pieces with titles evocative of nature – 'Reflets dans l'eau' (1905), 'Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir' (1910) and 'Brouillards' (1913) – and suggests that the Impressionist painters' use of brush-strokes and dots is paralleled in the music of Debussy. Although Debussy said that anyone using the term (whether about painting or music) was an imbecile, some Debussy scholars have taken a less absolutist line.

Lockspeiser calls La mer 'the greatest example of an orchestral Impressionist work', and more recently in The Cambridge Companion to Debussy Nigel Simeone comments, 'It does not seem unduly far-fetched to see a parallel in Monet's seascapes'. In this context may be placed Debussy's eulogy to Nature, in a 1911 interview with: I have made mysterious Nature my religion. When I gaze at a sunset sky and spend hours contemplating its marvellous ever-changing beauty, an extraordinary emotion overwhelms me.

Nature in all its vastness is truthfully reflected in my sincere though feeble soul. Around me are the trees stretching up their branches to the skies, the perfumed flowers gladdening the meadow, the gentle grass-carpeted earth,. And my hands unconsciously assume an attitude of adoration.

In contrast to the 'impressionistic' characterisation of Debussy's music, several writers have suggested that he structured at least some of his music on rigorous mathematical lines. In 1983 the pianist and scholar published a book contending that certain of Debussy's works are proportioned using mathematical models, even while using an apparent classical structure such as. Howat suggests that some of Debussy's pieces can be divided into sections that reflect the, which is approximated by ratios of consecutive numbers in the. Simon Trezise, in his 1994 book Debussy: La Mer, finds the intrinsic evidence 'remarkable,' with the caveat that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy deliberately sought such proportions. Lesure takes a similar view, endorsing Howat's conclusions while not taking a view on Debussy's conscious intentions.

Musical idiom. Chords from dialogue with Ernest Guiraud Debussy wrote 'We must agree that the beauty of a work of art will always remain a mystery. we can never be absolutely sure 'how it's made'. We must at all costs preserve this magic which is peculiar to music and to which music, by its nature, is of all the arts the most receptive'. Nevertheless there are many indicators of the sources and elements of Debussy's idiom.